The Paris Agreement, Part 2: The Good News and The Bad News

The Good News

Consider how difficult it is for the U.S. goverment to reach a political agreement on anything these days. It isn’t easy. Too much money funding politicians and causes has all but shut down the consensus building mechanism created by our founders. Now consider the likelihood of 197 nations with their own political systems coming together and agreeing on how to limit climate warming.

First, each nation has to see climate warming as a problem. Next, it’s government has to agree that something must be done on the international/global level and support the details of those actions. Not easy!

It is a testimony to the efforts of the U.N. that 190 nations formally joined the Paris Agreement. The hard part is for each country to do its share. Clearly the agreement is aspirational and it appeals to human emotion. It is a “feel good” agreement and it sets up the framework as discussed in Part 1 of this three part series.

There are many great features about the framework. There are ways to grade nations on their own commitments to reduce greenouse gas emissions. There is a requirement that each country better its commitment every 5 years. There are mechanisms for countries in a region to help struggling countries reach their commitment by sharing their excess performance with underperformers.

A financial mechanism to help fund projects that will help protect forests and other natural carbon sinks is a great feature of the agreement.

There is a clear understanding that the technologies from developed countries need to be deployed to help developing countries leapfrog their older technology so they can reach their goals.

All of this is a good start to addressing one of the most daunting problems of the 21st century. Now that 5 years has gone by its time for each country to make its new commitment that betters the one made in Kyoto in 2015.

Where Are We Today?

Let’s see how much progress has been made. First, we should consider the origins of todays greenhouse gas emissions.

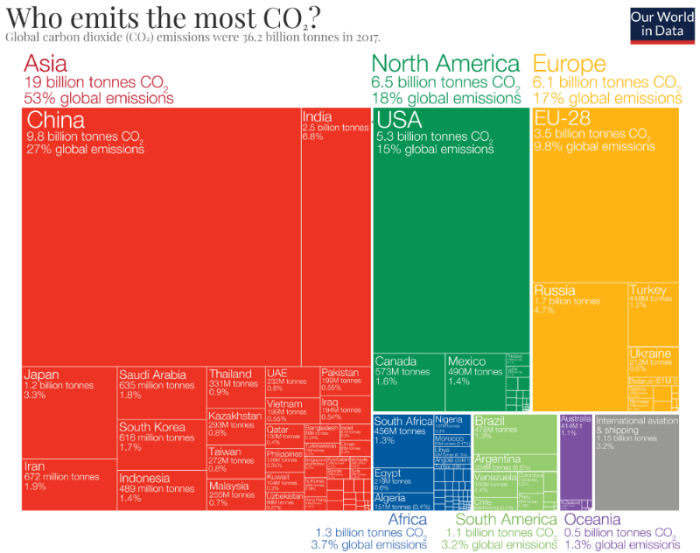

The countries emitting the majority of greeenhouse gases annually are:

- China 30% and growing

- USA 15% and declining

- EU 10% and stable

- Russia 5% and growing slowly

- India 7% and growing fast

- Japan 3% and declining

The following graphic shows the regional breakdown of 2017 CO2 emissions.

2017 Global CO2 emissions by country and region. Source: Our World in Data, graphic by Hannah Ritchie (CC BY)

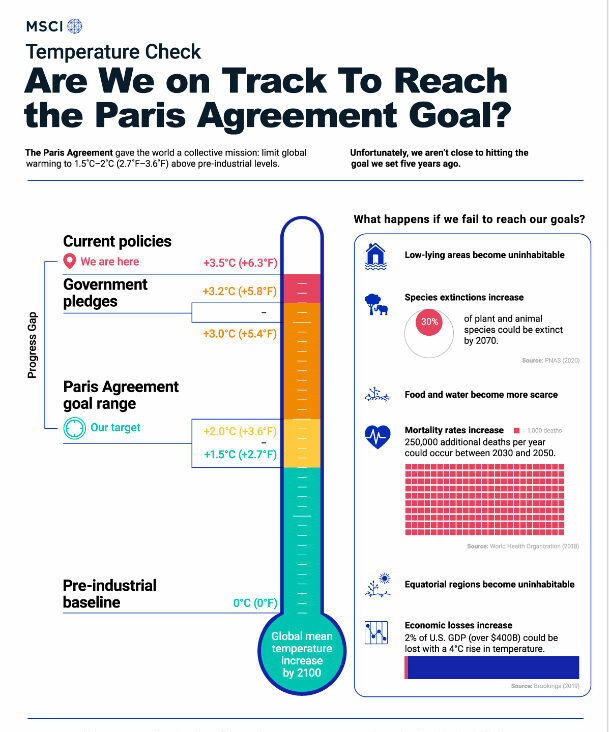

Next, let’s look at the actual pathway global temperatures are taking, given that the Paris Agreement is now entering its 6th year.

Notice the “Progress Gap” between the Paris Agreement goals and the current commitments to GHG emission reduction.

The Bad News

If we continue on the present path the climate will warm about 3.5°C (6.3°F) before temperatures level off. That is double the goal of the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, present commitments, if realized, would only improve results to a small degree with a projected 3°C temperature increase.

There are many reasons why we are so far behind at the moment, even though some progress is being made.

First, the framework was somewhat arbitrary in defining developed and developing countries. This distinction is key because developed countries are supposed to be reducing GHG emissions now and developing countries don’t have to bring a decrease until 2030.

The two biggest polluters are China and the U.S. China is considered a developing nation even though it’s the world’s second largest economy. The U.S. is considered a developed nation and has the largest economy. Japan and Europe as a whole are considered developed and India is considered developing.

China is increasing it’s CO2 emissions by 2% per year. In other words, the largest polluter has a growing share of GHG’s every year and it has no requirement to begin a decline until 2030.

While much has been made of the U.S. leaving the Paris Agreement and rejoining, in 2019 (the last year of data for a “normal” economy) the U.S. reduced its CO2 emissions at an annual rate of 2.9%. While other countries reduced their emissions at a faster rate, in absolute terms the U.S., with the world’s largest economy, made the greatest total reduction in emissions – 140 Mt.

Intellectual property is an issue that the agreement doesn’t meet head on. It is clear there is a problem with providing developing nations, especially China, with advanced technology so it can more quickly reduce its emissions. In order for that to happen, intellectual property has to be protected and paid for. Unless China and the developed world can agree on this important issue, progress that China can make by 2030 is being held hostage to its long practice of not recognizing intellectual property rights.

The bottom line is that China has to be brought into the developed nations club. The largest CO2 emitter by far can’t be exempt from carbon reductions for another 10 years if the world is going to get close to meeting its goal. Classifying China as a developing country was perhaps the worst decision in the drafting of the Paris Agreement. Following close behind is the failure to deal with Intellectual Property. Without protection, the most efficient technologies will not be available to the developing world to more rapidly reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and to promote rapid decreases in the years ahead.

Finally, the Green Climate Fund to help finance climate warming mitigation and adaptation, part of the Paris Agreement Financial Mechanism, is only being funded at about 10% of the annual goal of $100B. Annual funding of $100B is a literal drop in the bucket. Consider that the U.S. has spent $5.2T on its internal COVID response. Climate Warming is itself a global pandemic-like issue. Until the funding matches the rhetoric, progress will be more of a public relations story than actual success. While climate warming rhetoric has improved, financial backing has been pitiful. It’s time to walk the talk.

Stay tuned for Part 3: The Opportunity!