The Western U.S. Megadrought is the worst in 1,200 years

What is a Drought?

A drought is an unusual climate phenomenon, in that it is defined by the gradual loss of water, instead of suddenly changing conditions. Unlike fast developing, catastrophic events like tropical storms, droughts slowly develop over time, as the loss of water inexorably exceeds its rate of replacement by rain or snowfall in a sort of slow moving climate train wreck.

Climatologists actually identify four types of drought:

- meteorological – essentially a period of dry weather

- hydrological – when sustained or repeated meteorological drought results in diminished water supply, not only in surface water and reservoirs, but also in the form of reduced soil moisture and depleted groundwater

- agricultural – sufficient dry weather to negatively affect crop growth

- socioeconomic – links supply and demand of commodities to drought

Drought is a constant element of the U.S. climate. Since 1895, on average, about 14% of the U.S. has experienced moderate to severe drought in any given year. Droughts often last for several years, and occasionally a decade or more. The rare droughts lasting 20 years or more are referred to as “megadroughts.”

In this post we are interested in the ongoing megadrought in the Western U.S., and its connection to long term climate warming.

Climate Warming and Drought

Basically, the higher temperatures in a warming climate amplify water loss through evaporation of surface water and soil moisture, and increased water loss from vegetation. Thus a cooler climate is less susceptible to drying out in a low precipitation period.

At the same time, climate change is altering precipitation patterns around the world. While we are able to predict future warming, predicting seasonal, or even annual, precipitation for a specific location is notoriously difficult. However, on a more general level we know that currently “wet” regions, like the tropics, will get wetter, while dry areas like the subtropics will get drier still.

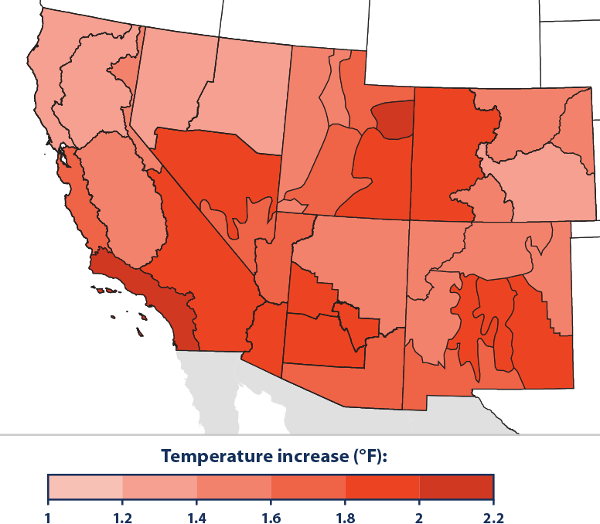

Global climate warming is steadily increasing drought risk in many regions of the world. In already hot and dry regions like the Southwestern U.S., droughts will be more frequent, more severe, and last longer. The Southwestern states have already seen a sustained decrease in annual precipitation since the early 20th century, and the trend is expected to continue. Temperatures have moved in the opposite direction, with the average temperature in the last two decades well above the long term average, as shown in the figure below.

The average air temperature from 2000 to 2020 is well above the long-term average (1895–2020) Source: EPA

The average air temperature from 2000 to 2020 is well above the long-term average (1895–2020) Source: EPA

Drought in the Western U.S.

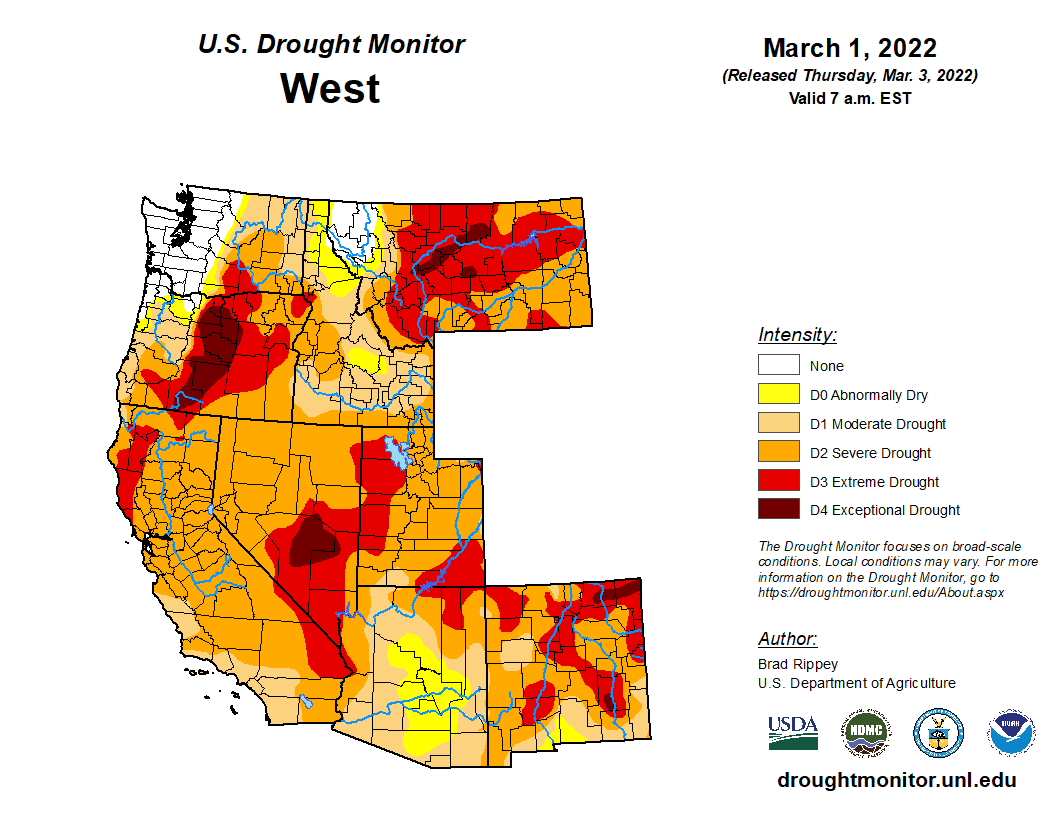

The Western U.S. has been in drought conditions since 2000, placing it solidly in megadrought territory. The Southwestern U.S. has been here before. Its naturally hot, dry climate is often amplified by La Niña events, which push the polar jet stream (and storm tracks) northward. However, the 2021 La Niña year saw the drought extending beyond the Southwest, marked by record high temperatures in the Pacific Northwest. In fact, the current megadrought covers most of the contiguous U.S. west of the continental divide.

As of this writing, over 95% of the U.S. West is experiencing drought conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. A promising early winter snowpack withered under an unusual January-February dry period. Numerous California locations set all-time low precipitation records for January-February, with San Francisco recording a mere 0.65 inches over the two winter months – only 7% of normal! Despite heavy snowfall in late 2021, by the end of February the Sierra Nevada snowpack was down to about 15 inches (less than two-thirds of the average for that date.)

The Colorado River Is In Trouble

Perhaps the Colorado River Basin best embodies the severity and impact of the western megadrought. The carefully managed basin provides water to millions of people—the cities of San Diego, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Los Angeles for example—and about 15% of the nation’s farmland. Fully 80% of the water is used for agricultural irrigation.

Heavily reliant on snowpack runoff from the Rockies and the Sierra Nevada, the region relies on reservoirs to manage the seasonal inflow through dry periods. In fact, the Colorado river feeds the two largest reservoirs in the U.S.—Lake Powell and Lake Mead—both of which are at record low levels. At the close of 2021, Lake Powell was at 31% capacity, with water levels more than 150 feet below “full”—its lowest level in 52 years. Lake Mead is at 35 % and 152 feet below the level when it was first filled in 1937.

In the past, both reservoirs have been regularly “topped up” by controlled release of water from smaller upstream reservoirs. Now, the entire Lower Colorado River water storage system is down to 39% of capacity and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation was forced to direct a reduction in downstream water releases from Glen Canyon Dam (Lake Powell) and Hoover Dam (Lake Mead) in 2022—the first-ever “shortage” declaration.

In an op-ed, the authors of the NOAA Drought Task Force Report on the Southwest’s drought highlighted its connection to climate warming: “[W]e found that this drought was triggered by an exceptional multi-season period of low rain and snowfall. The drought was intensified by extreme temperatures fueled by climate change that dried out soils, rivers and vegetation. It is projected to cause tens of billions of dollars in impacts.”

What Does Drought Look Like?

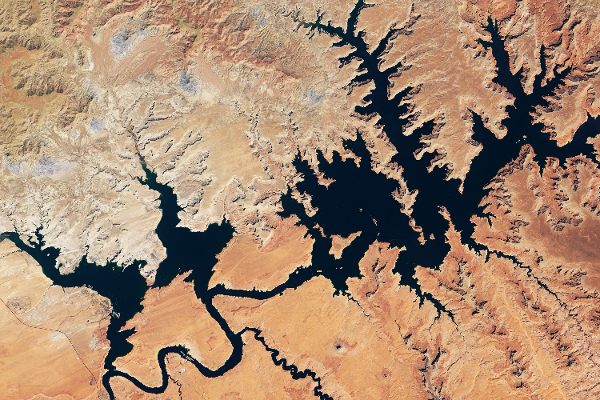

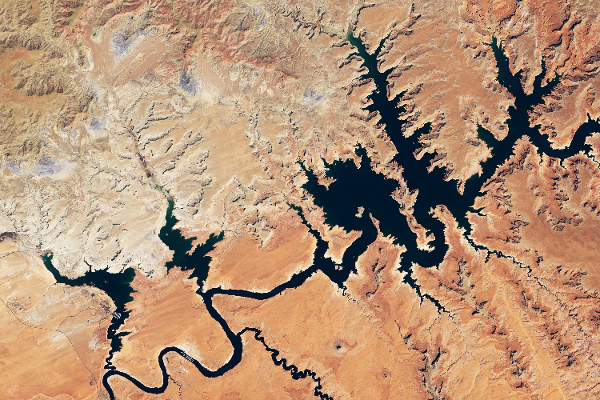

The following NASA images, both taken in late summer, show the recent dramatic changes in Lake Powell due to the unrelenting drought. The 2017 image shows Lake Powell at its highest level in the last decade—still well below its maximum. The 2021 image shows the lake 84 feet lower just four years later. The lake is now just over 50 feet above the minimum level needed to keep the Glen Canyon Dam hydroelectric generators operating. When the megadrought began in 2000, Lake Powell was nearly 150 feet higher than today.

Lake Powell 2017

Lake Powell 2021

How Bad Is It?

It turns out that this megadrought is exceptionally bad—the worst drought event in the region for at least 1,200 years. In research published last month in the journal Nature Climate Change the study team said that the extreme drought conditions of the last two years made the current megadrought the worst in the Western U.S. since 800 AD, when Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor of the West and feudalism began to spread across Europe.

Analyzing tree ring records from thousands of sites in western North America, and cross-checking with historical climate data, the researchers were able to estimate annual soil moisture conditions through the centuries. The study found that the region experienced four other megadroughts over the centuries, following natural climate variability, but none as severe as the current megadrought.

Analysis clearly showed the effects of anthropogenic (human caused) climate warming. The result? Since the current drought began in 2000, the study shows that the average soil moisture deficit was twice as severe as any drought of the 1900s, and more severe than the driest periods of the last 1200 years. In fact, the research attributes 42% of the soil moisture deficit since the current megadrought began in 2000 to the effects of climate change. In the words of lead author Park Williams, UCLA, “Without climate change, the past 22 years would have probably still been the driest period in 300 years. But it wouldn’t be holding a candle to the megadroughts of the 1500s, 1200s or 1100s.”

Predictions of the future are not enccouraging. In a Twitter post, Williams suggests “Background drying due to anthropogenic warming is likely to become increasingly dominant, requiring more and more good luck from ocean/atmosphere variability to break out of droughts, and less and less bad luck to make droughts longer and drier.” Study co-author Jason Smerdon, Columbia University, sums it up: “These multi-decade periods of dryness will only increase with the rest of the century.”

Why Is This Suddenly A Problem?

Human-caused climate warming on top of natural climate variability is only part of the West’s water problem. Decades of rapid population growth, coupled with millions of acres of agricultural irrigation, have reached the limits of the current water management system in the western states. This isn’t new. Marc Reisner’s landmark book, “Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water” captured the problem 35 years ago, before the implications of climate warming were well understood.

Unfortunately, the plans of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers to address the West’s water management needs, first by building the Hoover Dam (Lake Mead) in the 1930s, and when that proved insufficient, the Glen Canyon Dam (Lake Powell) in the 1950s, were founded on poor information. Not only was anthropogenic climate warming largely unknown at the time, but as Andrew Revkin points out in Sustain What, they had the bad luck to base their planning on the wrong piece of history.

As the tree ring research of Williams et al discovered, earlier Western U.S. megadroughts occurred in the 800s, 1100s, 1200s and 1500s—facts unknown to the water management planners of the early 20th century. Instead, their plans were based on the history of what Revkin calls the “megadrought gap”—the period from 1700 until the early 1900s. In an interview by Revkin, Williams summed it up: “The one thing that we were suckered by is the fact that there wasn’t a naturally occurring megadrought during the 1800s or 1900s. And so the backstops that we built to safeguard against the worst droughts weren’t actually built to be able to withstand the worst droughts.”

The Future Looks Hotter and Drier

Where do we go from here? In the short term, it is likely that the drought will continue through 2022. It will take multiple wet years to break a drought this severe. Inevitably, natural climate variability will extricate us from this particular megadrought. Unfortunately, global climate warming is showing no signs of letting up for a while, ensuring that there are more frequent and more severe droughts in the future of the American West, and the future of drought-susceptible regions worldwide.

“Climate change is changing the baseline conditions toward a gradually drier state in the West and that means the worst-case scenario keeps getting worse.” Park Williams