Another Year of Climate Warming

Progress Since COP26

The 2021 U.N. Conference of the Parties to the Paris Agreement,COP26, was held in Glasgow, Scotland. Under its British presidency, COP26 set aggressive goals and commitments for greenhouse gas emissions and support for developing countries struggling to adapt to the effects of climate warming. The flagship goal of COP26 was “secure global net zero by mid-century and keep 1.5 degrees within reach” — abbreviated to the popular slogan “Keep 1.5 Alive.”

Image Credit: UNFCC CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0

Heading into COP27 a year later, the enthusiasm of 2021’s COP26 has evaporated in the turmoil of war in Ukraine, the global energy crisis, global inflation and a developing global recession.

At COP26, all countries agreed to revisit and strengthen their climate plans by COP27 in 2022. In the event, only 24 out of 193 nations submitted updated plans to the UN. Similarly, companies with net zero emissions commitments have failed to back those pledges with plans matching their words.

What’s the result? Well, in 2021 Global greenhouse gas emissions were 40.8 billion metric tons. In 2022, the estimated total emissions will be 40.5 billion tonnes, a level roughly unchanged since 2015. While stabilizing emissions is a success of sorts, the reality is that these levels far exceed the capacity of the land and oceans to absorb emissions out of the atmosphere. Consequently, atmospheric CO2 levels continue to rise, and climate warming marches on.

Meanwhile, in 2022 the world experienced a series of climate warming-related/influenced disasters: catastrophic flooding in Pakistan and Nigeria; heat waves, drought and forest fires in Europe; a devastating drought in East Africa; and one of the costliest Atlantic hurricane seasons on record.

And so the stage was set for COP27.

A Tumultuous COP27

The 27th Conference of the Parties took place for the first time on the African continent, in Sharm el-Sheik, Egypt, with the over-arching theme of “delivering for people and the planet.” Over two weeks in November, over 35,000 participants worked to find consensus on a way forward.

In his keynote address at COP27, UN Secretary-General António Gutteres called climate change “the central challenge of our century,” stating “the fight for a liveable planet will be won or lost in this decade.”

We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator — António Gutteres

The COP27 presidency of host country Egypt, defined four goals for the conference:

- Mitigation: limit global warming to well below 2ºC and work to keep the 1.5ºC target alive

- Adaptation: enhancing resilience and assisting the most vulnerable communities

- Finance: address the adaptation needs of developing countries, the Least Developed Countries, and Small Island Developing States

- Collaboration: an inclusive “all hands on deck” approach

So, how did it go?

Going into the conference, wealthy and poor countries were at odds, as big economies have been too slow to cut greenhouse gas emissions, while the poorer countries most impacted by the climate crisis receive little of the financial assistance promised for adaptation and resilience.

The Paris Agreement committed rich countries to contribute $100 billion per year to assist poor countries with mitigation and adaptation. In the seven years since, the commitment has never been met. Hence the “Finance” goal of COP27.

Finance quickly became the defining element of the conference. Key to the negotiations was the issue of “loss and damage” — the consequences of the worst impacts of climate change, which are too severe for less developed countries to adapt to.

Poor countries experiencing loss and damage need access to funding to rebuild when climate disasters such as extreme hurricanes, floods and droughts strike. COP27 focused on getting loss and damage financing back on track with an emphasis on adaptation — providing poor countries the financial resources to adapt to the climate change the developed countries have caused.

COP27 Results

Heated negotiations finally resulted in an ageement to establish a dedicated “Adaptation Fund,” intended to compensate vulnerable nations for loss and damage from disasters related to climate change. However, the details of the fund’s structure and financing are still to be determined.

With the focus on “loss and damage,” there was very little progress on mitigation and the “keep 1.5 alive” goal. Despite the inexorable rise in atmospheric CO2 levels, Saudi Arabia, China and others blocked attempts to set more aggressive goals for fossil fuel cutbacks.

On a more hopeful note, a small group of countries, led by Denmark and Costa Rica, addressed the fossil fuel elephant in the room by announcing their creation of the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA).

The goal of BOGA is nothing less than a managed phase-out of oil and gas production. Core members include Portugal, Washington State, France, Greenland, Ireland, the Province of Quebec, Sweden, and Wales. They are committing to no new licensing for oil and gas exploration and extraction, and an end date for production in line with the Paris Agreement.

COP27 and 1.5ºC

The Paris Agreement’s long term goals of limiting global warming to well below 2ºC and pursuing 1.5ºC (to avoid increasingly severe climate impacts) were restated at COP27. And reinforced by the COP26 theme “Keep 1.5 Alive.” But talk is cheap and the reality is that we have made little progress to realizing the goals set in 2015.

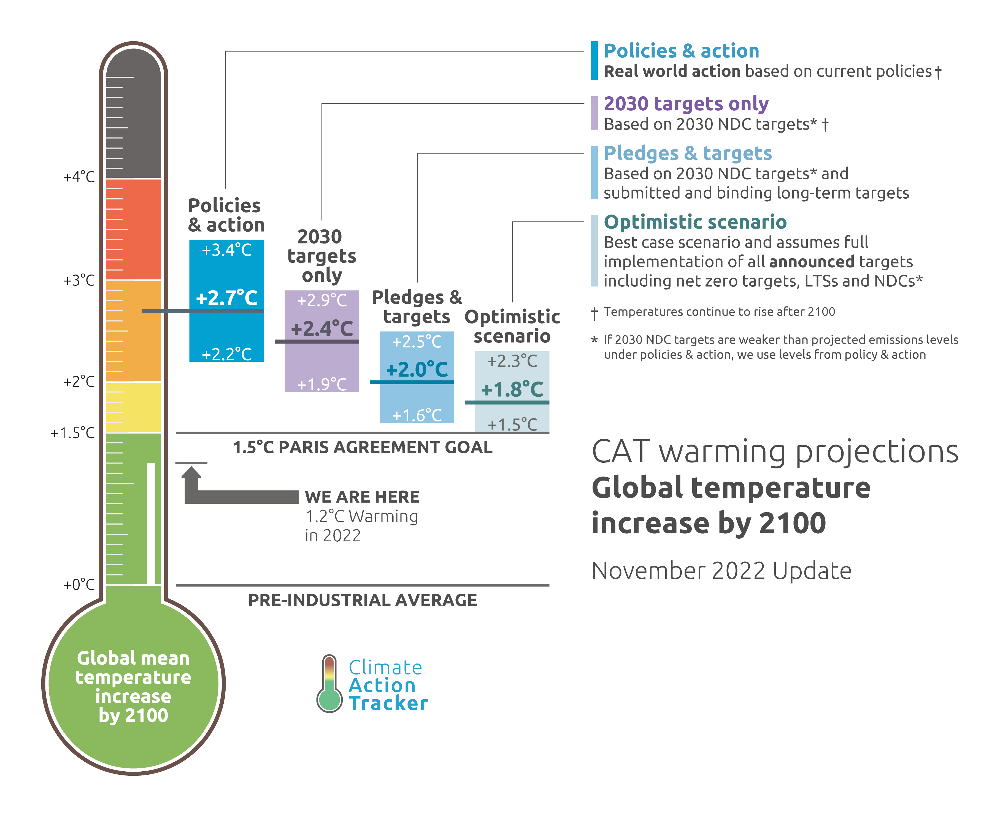

After COP27, Climate Action Tracker updated their climate warming estimates for the rest of the century, based on four scenarios, ranging from real world action based on established government policies to an optimistic “best case” scenario. The results are shown in the figure below.

Source: Climate Action Tracker

The chart shows that continuing with current government policies and actions around the world will blow right through the Paris Agreement targets. (Note that the predicted temperatures on the CAT thermometer are median values of the range of estimates — the 50/50 probability point. Half of the estimaes are lower than the median and half are higher. Thus the Policies & action scenario estimates range from 2.2ºC to 3.4ºC, with a median of 2.7ºC.) Current “Policies and Actions” will lead to a global average temperature in 2100 well over the 2ºC target, and possibly over 3ºC.

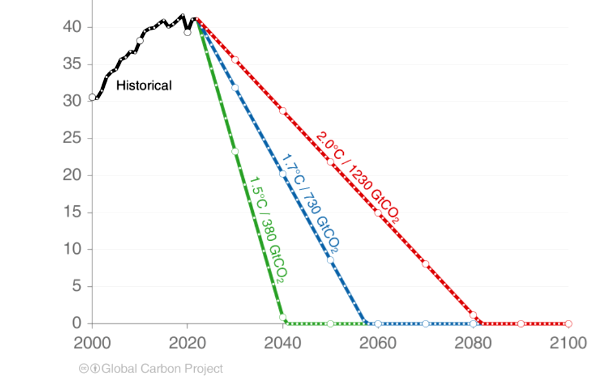

What about the 1.5ºC goal? Estimates by the Global Carbon Project place the remaining “carbon budget” for 1.5ºC – that is, the amount of CO2 that can still be emitted for a 50% chance of staying below 1.5ºC of warming – at 380 gigatonnes of CO2 (GtCO2). (A gigatonne is a billion metric tons.) At our current rate of emissions of more than 40 GtCO2 per year, we will exhaust this budget in just nine years.

Cutting global CO2 emissions to zero by 2050, in line with limiting warming to 1.5ºC, would require them to fall by about 1.4GtCO2 every year. This is roughly the same as the drop in emissions in 2020 as a result of worldwide COVID-19 lockdowns. Put another way, global emissions will have to fall by almost 50% by 2030 to “keep 1.5 alive.”

As the graphic below demonstrates, keeping 1.5 alive would require an unrelenting and precipitous decline in CO2 emissions.

Image Source: Global Carbon Project (CC-BY)

As the saying goes, “you can’t get there from here.” The United Nations’ Environment Programme’s 2022 emissions report flatly states that there is “no credible pathway” to limiting global warming to the 1.5ºC target.

Within the next five years, it is likely that we will experience our first year with a global average temperature 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels. Once we get there, a year after year average of 1.5 is just around the corner, likely no later than the 2030s.

This is certainly worrisome, but it is far from the end of the world. 1.5ºC was always an aspirational target — a stretch goal. Changes to the climate are on a continuum — we don’t fall off a cliff when the temperature exceeds 1.5ºC. As climate scientists are fond of saying “every tenth of a degree matters.” We’re already experiencing climate impacts at 2022’s 1.2ºC, and they will be worse at 1.5ºC and still more serious at as temperatures continue to climb. (We’ll discuss just how serious later in this article.)

But for some people, 1.5ºC is very important, indeed.

Why is 1.5ºC so important?

The origin of the 1.5º and 2ºC targets enshrined in the Paris Agreement owes more to 2015 diplomacy and realpolitik than to hard science. At the time, 2ºC was agreed by the developed countries to be a threshold above which our interference with the climate system might become dangerous. However, “dangerous” is in the eye of the beholder. A group of poor countries and Small Island Developing States held out for 1.5ºC because sea level rise at warmer temperatures would inundate their low-lying communities. In order to achieve a consensus, the parties finally agreed not only to a “well below” 2ºC target, but also to “pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C.”

Seen through the lens of 2022’s climate disasters, 1.2ºC of warming is already proving pretty dangerous. Given that, it’s tempting to predict that every tenth of a degree warmer might make things just a little bit worse. Unfortunately, it’s more complicated (and worse) than that.

The problem lies in “tipping points” that exist within elements of the Earth system. In fact, we will see that climate tipping points are critically sensitive to climate warming at 1.2ºC and above.

Tipping Points

The concept of tipping points originated in the ominously named branch of mathematics called Catastrophe Theory. In general terms, a tipping point is defined as a point at which slow, reversible change becomes irreversible, often with dramatic consequences. A tipping point example in a natural system is an avalanche. The snow on a steep slope is stable as the buildup of snow slowly approaches and then reaches the tipping point, and the irreversible snowslide that results is definitely a “dramatic consequence.”

Climate system tipping points are on a much slower timescale and impact a much larger region. As climate warming pushes the system beyond the tipping point the system can develop a positive feedback loop, rendering the system change “self-perpetuating,” and thus irreversible.

In 2000, author Malcolm Gladwell popularized the sociological application of the tipping point concept with his best seller “The Tipping Point – How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference.” Around the same time, the concept of climate system tipping points was introduced into mainstream climate change policy discussions by the Intergovermental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). At that time. large scale climate change tipping points were thought to be associated with global climate warming exceeding 5ºC above pre-industrial levels. As a result, tipping points were unfortunately not a major concern in crafting the Paris Agreement.

Ongoing research and improved climate models summarized in recent IPCC Reports suggests that tipping points could be exceeded even between 1 and 2ºC of warming. The IPCC judges the risk of these events occurring is high around 2ºC and becomes very high in the range 2.5-4ºC.

This means that the 1.5ºC target is back in the spotlight. Every tenth of a degree matters because we are navigating a potential minefield of climate tipping points as climate warming climbs beyond today’s 1.2ºC.

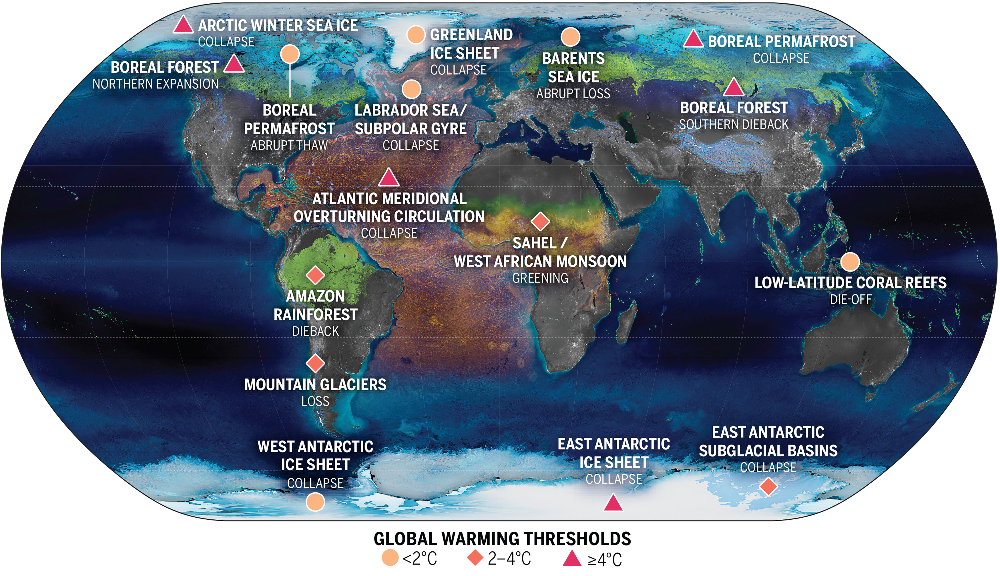

A research team led by David Armstrong McKay recently published an analysis of the elements of the global climate system at risk, their climate tipping points, and the timescales and impacts of crossing the tipping point. The results are summarized in the figure below.

Tipping Elements in the Earth system. Source: Armstrong McKay et al (2022)

The map shows the location of climate tipping elements in the cryosphere (blue), biosphere (green) and the ocean/atmosphere (orange). The global warming levels at which the tipping points will likely be triggered are indicated by colored markers: below 2ºC (in the Paris Agreement range) – light orange circles; between 2 and 4ºC (committed by current policies and actions) – orange diamonds; and 4ºC and above – red triangles.